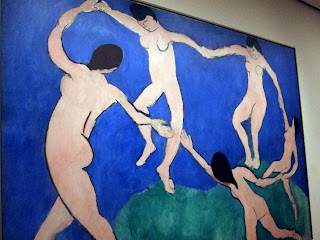

I can't believe it's been months since I last blogged! I'd like to say that it was because my life was full to bursting with dazzling adventures, social whirl, glamorous night life, but the reality is I have been tentatively feeling my way here in NJ. Slowly, slowly. Inch by inch. Appreciating tiny things: the crystal clear view of the sky and its constellations from my huge backyard (Geminid showers 3 AM this morning; setting my alarm!); Doris, the talkative 75 year old crossing guard who loves Rosie and wants to "introduce her to other dogs in the neighborhood;" singing the "12 Days of Christmas" with mom as we set up the Fagan family tree; glorious MOMA and Matisse with his rapturous dancing nudes on a blue background.

But, I've also been reading a LOT--and as often happens when I read a LOT, synapses start firing and throwing off sparks and ideas in a new book will flint and flame and send off other sparks until there's a veritable firework fountain in my head. And what I've been paying most attention to lately (though I've never felt less focused in my life) is, ironically, the act of paying attention, or more precisely, what it is that captures my focus and what that might say about my life.

On Plums and Dogs and Paying Attention

Winifred Gallagher's book Rapt: Attention and the Focused Life engaged my own frequently divided, scattered, and diffused attention immediately in her first two paragraphs:

Five years ago, a common enough crisis plunged me into the study of the nature of experience. More important, this study led me to cutting-edge scientific research and a psychological version of what physicists call a "grand unified theory"...: your life--who you are, what you think, feel and do, what you love--is the sum of what you focus on.

That your experience largely depends upon the material objects and mental subjects that you choose to pay attention to or ignore is not an imaginative notion, but a psychological fact. When you focus on a STOP sign or a sonnet, a waft of perfume or a stock market tip, your brain registers that "target" which enables it to affect your behavior. In contrast, the things you don't attend to in a sense don't exist, at least for you. All day long you are selectively paying attention to something, and much more often than you may suspect, you can take charge of this process to good effect. Indeed, your ability to focus on this and suppress that is the key to controlling your experience and ultimately, your well-being.

I'm a big fan of books exploring neuroscience and behavioral science, but this book has also deeply resonated with me for many reasons right now. 1.) I've been struggling to find my focus since my move. 2.)As a poet, I've known that this conscious act of paying specific attention to the world--for instance, in my one chapbook, the shadowy, nuanced environment of alleyways--has deeply shaped my work 3.) And I've often encouraged my students (as many poetry teachers do) with Zen exercises and "object" exercises to help them sharpen their focus, and tune into the details of their world. And what they choose to write about, to turn their focus to: the drunk man swearing on the 61-C bus or their grandmother's engraved silver hairbrush lying in a cardboard box begins to help them understand what it is they value. What you pay attention to as a writer is what you ask your reader to pay attention to: hey, folks, look at this. this matters!